by Dr. Jack Kilcrease

Harry, Carolus Powel. Protest and Progress in the Sixteenth Century. Philadelphia: Joint Lutheran Committee on Celebration of the Quadricentennial of the Reformation, 1917.

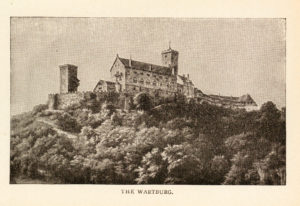

Luther recognized that his failure to recant at the Diet of Worms (April, 1521) had put him in very serious danger. For this reason, after his defiant confession of faith before the Emperor, he was rushed away back to Wittenberg by coach. On the way back, he was overtaken by a group of Frederick the Wise’s guards disguised as highwaymen. They escorted the Reformer back to Wartburg Castle where he would remain for the next ten months. Wartburg Castle was a hunting castle that belonged to the ducal family of Saxony. To the present day, it lies in the Thuringian forest in north-central Germany.

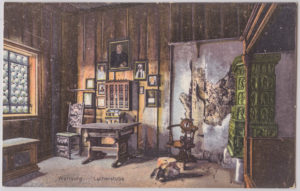

For his quarters, Luther was given a single room for work, along with a rather narrow adjoining bedroom. This bedroom and living quarters were located in the northern bastion above the dwelling place of Hans von Berlepsch, the fortress’ Burgmann (English: “lord of the castle”). Normally, this was the area of the castle where prisoners were kept if they were knights.

Luther’s location in this castle was kept an absolute secret. Indeed, even Duke John (Frederick the Wise’s brother) did not realize Luther’s location until he happened to visit the castle in September, 1521. To add further to the secrecy, Luther grew a beard and began to call himself by the alias “Junker Jörg” (Knight George).

Luther’s location in this castle was kept an absolute secret. Indeed, even Duke John (Frederick the Wise’s brother) did not realize Luther’s location until he happened to visit the castle in September, 1521. To add further to the secrecy, Luther grew a beard and began to call himself by the alias “Junker Jörg” (Knight George).

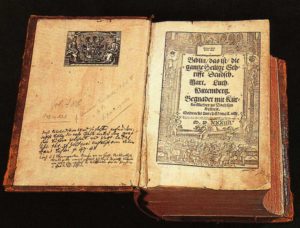

Although Luther was in hiding during this period, it did not mean that he entirely stopped his scholarly and reforming activity. Indeed, the Reformer busied himself with a number of important matters. The first of these was Luther’s translation of the New Testament from koine Greek to German. To do this, Luther used Erasmus’ 1516 edition of the Greek New Testament. Helpfully, Erasmus had constructed his edition so as to juxtapose the original Greek text on one page with his own fresh Latin translation on the other. This allowed Luther to compare his own German rendering to Erasmus’ own contemporary Latin translation of the text. Similarly, there were annotations in the Erasmus’ edition which highlighted where the original Greek text differed from the Vulgate, the standard Latin translation of Bible in the Middle Ages.

Beyond his translating activities, Luther also had to contend with attacks from his theological opponents. During this period, he was attacked in print by Jerome Emser, Albrecht of Mainz, and even another papal bull. Although Luther increasingly found most of his opponents unworthy of his time, he did nonetheless take a great deal of effort to respond to one, namely, the scholastic theologian Jacobus Latomus of Louvain University. This was ultimately a worthy effort, insofar as Luther’s Against Latomus (1522) proved itself to be a masterpiece of Reformation theology. It is very likely one of the most systematic and clear presentations of the central principles of the Reformation written by Luther prior to the Bondage of the Will (1525).

Beyond his translating activities, Luther also had to contend with attacks from his theological opponents. During this period, he was attacked in print by Jerome Emser, Albrecht of Mainz, and even another papal bull. Although Luther increasingly found most of his opponents unworthy of his time, he did nonetheless take a great deal of effort to respond to one, namely, the scholastic theologian Jacobus Latomus of Louvain University. This was ultimately a worthy effort, insofar as Luther’s Against Latomus (1522) proved itself to be a masterpiece of Reformation theology. It is very likely one of the most systematic and clear presentations of the central principles of the Reformation written by Luther prior to the Bondage of the Will (1525).

Luther begins the treatise with a defense of his paradoxical claim that “every good work is a sin.” Luther does this with reference to the biblical text Isaiah 64:6: “. . . all our righteous deeds are like a polluted garment”. Luther’s point here is not to discourage good works nor to say they are of no value. Rather, following St. Augustine, Luther points out that in the eyes of God, works do not make a person good or evil. Instead, works are performed out of the good or evil present in one’s heart. A person of faith is a good tree that bears good fruit. Even if an unbeliever’s works appear pure, those works are in reality bad fruit from a corrupt tree (Mt. 7:17-18). Nevertheless, although faith does produce good works and cleanses our inner person, it is not by this inner cleansing that faith appropriates salvation. Believers are indeed genuinely sanctified, but at the same time they remain sinners until their temporal death (simul iustus et peccator). Ultimately, faith saves because it takes hold of Christ, who has paid for all sins and imputes his righteousness to sinners.

Despite the great danger to his person, Luther eventually left the Wartburg and returned to Wittenberg in 1522. In his absence, the young Philipp Melanchthon had taken over the work of reform, but was ultimately not able to control the more radical elements within the city. Luther’s colleague at the university, Andreas von Karlstadt, began to preach a radical program of iconoclasm. This is involved smashing of statues and the destruction of images at the local churches by mobs. Karlstadt also prohibited a number of traditional ceremonies and began to teach a symbolic view of the Lord’s Supper. Along with Karlstadt, there appeared in the city a group of men called the “Zwickau Prophets.” This group claimed to be directly inspired by the Holy Spirit, and therefore also the ability to reveal God’s will apart from Scripture. Because events had gotten so far out of hand, Luther believed that it was essential to return to the city restore order. In returning, the Reformer was able to end the disturbances and resume his reforming activity.

Despite the great danger to his person, Luther eventually left the Wartburg and returned to Wittenberg in 1522. In his absence, the young Philipp Melanchthon had taken over the work of reform, but was ultimately not able to control the more radical elements within the city. Luther’s colleague at the university, Andreas von Karlstadt, began to preach a radical program of iconoclasm. This is involved smashing of statues and the destruction of images at the local churches by mobs. Karlstadt also prohibited a number of traditional ceremonies and began to teach a symbolic view of the Lord’s Supper. Along with Karlstadt, there appeared in the city a group of men called the “Zwickau Prophets.” This group claimed to be directly inspired by the Holy Spirit, and therefore also the ability to reveal God’s will apart from Scripture. Because events had gotten so far out of hand, Luther believed that it was essential to return to the city restore order. In returning, the Reformer was able to end the disturbances and resume his reforming activity.

Dr. Jack Kilcrease is a member of Our Savior Lutheran Church, Grand Rapids, Mich.