by Rev. Matthew Zickler

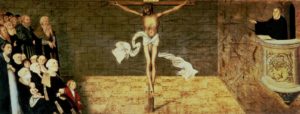

CRUX sola est nostra Theologia.[1] “The CROSS alone is our theology.” As Luther spoke those words during his lectures on the Psalms which took place between 1519-1521, he spoke words which utterly summed up the battle he was experiencing. This was about the cross of Christ. It was about the total inability of man to earn any of his own merit before God. It was about Jesus earning the salvation of all mankind as He was hanged, cursed on the bloody instrument of the tree of death.

CRUX sola est nostra Theologia.[1] “The CROSS alone is our theology.” As Luther spoke those words during his lectures on the Psalms which took place between 1519-1521, he spoke words which utterly summed up the battle he was experiencing. This was about the cross of Christ. It was about the total inability of man to earn any of his own merit before God. It was about Jesus earning the salvation of all mankind as He was hanged, cursed on the bloody instrument of the tree of death.

Merely months earlier in 1518, Luther had introduced this general idea in his thesis discussed at Heidelberg. In these Heidelberg Theses, he began to hash out the “Theology of the Cross,” and with it what it means to be a “Theologian of the Cross.” He began to explicate just what it means that the cross alone is our theology. As he did this, the two theses that perhaps capture his understanding the best are the 19th and 20th theses:

König, Gustav Ferdinand Leopold. 1900. The life of Luther in forty-eight historical engravings. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House.

19. That person does not deserve to be called a theologian who looks upon the invisible things of God as though they were clearly perceptible in those things which have actually happened [Rom. 1:20].

20. He deserves to be called a theologian, however, who comprehends the visible and manifest things of God seen through suffering and the cross.[2]

To our modern ears, we might hear this and think two things: 1) The Lutheran question, “What does this mean?” and 2) “What does this have to do with me?” To answer the first, Luther is making the point that as we look at the world, we often think we can understand who God is. In fact, we think that we can know Him and even perhaps connect with Him in some way. Being the sinners that we are, of course, we focus on the things we estimate to be good. We can “feel” so close to God when we go hiking in the beauty of the Rocky Mountains, or when we experience the love of our children as we nuzzle them in their beds before kissing them good night. This is to “look upon the invisible things of God as though they were clearly perceptible in those things that have actually happened.” We look at these things we like and assume that must mean that we have earned God’s pleasure and so deserve to be in heaven with Him. To be sure, these are good things, but why do we assume God’s pleasure with us in these things? Why do we make these assumptions, all the while ignoring what would have to be said of the hikers who die in avalanches or the nights where our children cry themselves to sleep in the midst of selfish tantrums?

Why? Because we are by nature no theologians. We by nature have no real desire to see God for who He actually is. As Paul says, quoting the Psalms, “As it is written: ‘None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one.’”[3] No one understands. NO ONE. No one seeks God. NO ONE.

In light of this, we must turn and become theologians. We must understand God not only the things we like, but through the things we do not like. However, when confronted with these, we turn tail from Him and run. Why? Because what we are confronted with terrifies us. We do not like confronting the evils of this world because it means that we have to consider the possibility that we ourselves are evil. When we think about the hikers who die or our children’s tantrums, it forces us to acknowledge that this world is no utopia.

In light of this, we must turn and become theologians. We must understand God not only the things we like, but through the things we do not like. However, when confronted with these, we turn tail from Him and run. Why? Because what we are confronted with terrifies us. We do not like confronting the evils of this world because it means that we have to consider the possibility that we ourselves are evil. When we think about the hikers who die or our children’s tantrums, it forces us to acknowledge that this world is no utopia.

A few weeks ago, we were confronted with one of the worst possible challenges as Christians: A mentally unstable man walked through the doors of a church and took the lives of 26 people. How do we look at this? What does this seem to tell us about God? How can we trust that God loves us, that He is good, especially if He does not even keep His people safe in His own house?

The reality is, we do not know what this says about God explicitly. We do not know why God allowed the deaths of those 26 poor souls. We do not know just what God’s purpose is in this situation, nor do we know what His plan is for those who have been left in mourning. To attempt to determine more would be to try to understand the invisible things of God through visible things. Luther would call this being a theologian of glory. This is wanting to see God’s glory like Moses did, while God is telling us we cannot see His face and live.

So, what do we do as theologians of the cross? We comprehend “the visible and manifest things of God seen through suffering and the cross.” What does that mean? We look at the cross of Jesus to understand God. We look at the bloodied God who was hanged on that tree of death and understand that He was hanged because God is angry about death, angry about the 26 deaths in Texas. He is angry about those deaths, about your death, about all death. He is angry about death because this is not what He wanted for the world. Death not the end for which He created the world when He first looked upon it and called it “very good.” He made it for life because He is the God of life and of the living.

So, what do we do as theologians of the cross? We comprehend “the visible and manifest things of God seen through suffering and the cross.” What does that mean? We look at the cross of Jesus to understand God. We look at the bloodied God who was hanged on that tree of death and understand that He was hanged because God is angry about death, angry about the 26 deaths in Texas. He is angry about those deaths, about your death, about all death. He is angry about death because this is not what He wanted for the world. Death not the end for which He created the world when He first looked upon it and called it “very good.” He made it for life because He is the God of life and of the living.

What then do we see on the cross? We see that this God loves this world. We see that this God has chosen to enter this world to suffer alongside those who suffer. Jesus, God in human flesh, knows what it means to be executed at the hands of sinful men. Jesus knows far more than any of us the trauma that those husbands and wives, parents and children, brothers and sisters experienced. He is with us in our suffering. However, what we see even more clearly is that Jesus has not only suffered with us, He has suffered for us. He is the God who died for us. He is the God of love who made Himself nothing so that He could serve sinful men.

In other words, as we look at the cross, we see the glory and majesty of God in His love for us. Luther, in explaining the 20th thesis of the Heidelberg Disputation says, “It does [a person] no good to recognize God in his glory and majesty, unless he recognizes him in the humility and shame of the cross.” In other words, when we look at the cross, there we can truly understand who God is, and apply that understanding to the rest of the world. We can look at the suffering of this world and see not only the sadness that comes with it, but we can see the God who has become a man of sorrows so that we would have the joy of eternity. To be sure, this does not mean that this life will always be easy. It will not, but it makes it a whole lot more bearable. Even still, this can only be comprehended in the cross of Jesus. The cross alone is our theology.

In other words, as we look at the cross, we see the glory and majesty of God in His love for us. Luther, in explaining the 20th thesis of the Heidelberg Disputation says, “It does [a person] no good to recognize God in his glory and majesty, unless he recognizes him in the humility and shame of the cross.” In other words, when we look at the cross, there we can truly understand who God is, and apply that understanding to the rest of the world. We can look at the suffering of this world and see not only the sadness that comes with it, but we can see the God who has become a man of sorrows so that we would have the joy of eternity. To be sure, this does not mean that this life will always be easy. It will not, but it makes it a whole lot more bearable. Even still, this can only be comprehended in the cross of Jesus. The cross alone is our theology.

The Rev. Matthew Zickler is pastor of Grace Lutheran Church, Western Springs, Ill.

[1] WA 5.176.32

[2] LW 31: 40.

[3] Romans 3:10-12