by Rev. Stephen Preus

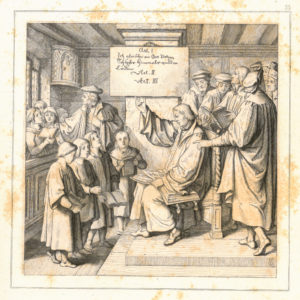

Picture yourself sitting in Luther’s house. It’s Sunday, late in the day and many others are gathered with you in the old Augustinian monastery-turned-parsonage in Wittenberg. Around you sits Katie, Luther’s beloved, and their six children. An assistant at the parish church, Georg Roerer, stands across the table ready with pen and paper in hand to copy whatever Luther says. So does Veit Dietrich, Luther’s assistant.[1] A few students and colleagues of Luther have joined you too, their eyes fixed on the great Reformer and their ears ready to hear him exposit the Scriptures. Then Luther reads the historic lesson for the day and proceeds to preach a sermon.

Picture yourself sitting in Luther’s house. It’s Sunday, late in the day and many others are gathered with you in the old Augustinian monastery-turned-parsonage in Wittenberg. Around you sits Katie, Luther’s beloved, and their six children. An assistant at the parish church, Georg Roerer, stands across the table ready with pen and paper in hand to copy whatever Luther says. So does Veit Dietrich, Luther’s assistant.[1] A few students and colleagues of Luther have joined you too, their eyes fixed on the great Reformer and their ears ready to hear him exposit the Scriptures. Then Luther reads the historic lesson for the day and proceeds to preach a sermon.

From 1531 to 1535 Luther delivered many of these sermons, what are known as his Hauspostille (house postils). The word “postil” comes from the Latin post illa verba textus, which means “after these words of the text.” Luther, like every Christian father, was the spiritual head of his household, and these sermons were meant not as a replacement for the Sunday Divine Service but as a devotional supplement. In fact, so much did Luther believe that fathers needed to be the heads of their households, that from 1521-1525 he wrote what are known as his Kirchenpostille (church postils). These were written for fathers to use as devotional material in their households, as well as for pastors to use for aid in sermon preparation. Just as Luther expected the head of the household to teach the Catechism to his children, so he desired them to have devotions with them, a practice that Luther was eager to do himself.[2]

For a time before 1531 Luther had filled the pulpit at St. Mary’s in Wittenberg while the regular parish pastor, Johannes Bugenhagen, was away instituting liturgical reforms. When Bugenhagen returned Luther’s preaching duties naturally decreased. In fact, the historical records relay that he “experienced persisting illness, fatigue, and weakness during these years [of 1531-1535], and thus only seldom felt well enough Sunday mornings to occupy the pulpit in the town parish church….”[3] Eugene Klug relates how the Hauspostille fit into this historical tidbit:

For a time before 1531 Luther had filled the pulpit at St. Mary’s in Wittenberg while the regular parish pastor, Johannes Bugenhagen, was away instituting liturgical reforms. When Bugenhagen returned Luther’s preaching duties naturally decreased. In fact, the historical records relay that he “experienced persisting illness, fatigue, and weakness during these years [of 1531-1535], and thus only seldom felt well enough Sunday mornings to occupy the pulpit in the town parish church….”[3] Eugene Klug relates how the Hauspostille fit into this historical tidbit:

Apparently, as a true and faithful preacher, [Luther] never felt fulfilled until he had shared pertinent and timely thoughts for the day on the basis of the standard Gospel lesson for the church year with the members of his household and devoted circle of friends. In one of his recorded comments at the table, he states that he considered it his duty to do so, both by virtue of his office and as a responsible father in his house.[4]

Luther usually did not preach these house sermons extemporaneously. Rather, he studied the text beforehand and delivered his sermon from an outline he had prepared. His outline contained specific concepts of the text that he wanted to get across to his family and friends. Centered on Christ for us in His life, death, and resurrection, the sermons comforted his family and taught them the ways and works of our Lord Jesus.

König, Gustav Ferdinand Leopold. 1900. The life of Luther in forty-eight historical engravings. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House.

So get yourself a copy of Luther’s Hauspostille, and cross the threshold of Luther’s house through the sermons that once entered the ears of his family and friends. They are well worth reading today not only for pastors, but for fathers around the dinner table or for family devotions or in the dorm room or all by yourself. With Christ at the center, faithful biblical expositions, and practical teaching throughout, you cannot go wrong with these house sermons of our father in the faith.[5]

The Rev. Stephen K. Preus is pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church, Vinton, Iowa.

[1] We have these men, Roerer and Dietrich, to thank for the preservation of these house sermons. Without the convenience of our modern voice recorders or typewriters, they faithfully took notes and transcribed them later for publishing. While we today might wonder how accurate they are, it was said that Luther “was a deliberate speaker who spoke slowly and distinctly, a characteristic which would have allowed time for an expert note-taker to do his recording” (The Complete Sermons of Martin Luther, Vol 5, 14).

[2] Roerer even included for the reader of Luther’s Hauspostille “General Guidelines for Leading Worshipers in Prayer at the Conclusion of the Sermon,” which were drawn from Luther’s comments about prayer in his sermons. See The Complete Sermons of Martin Luther, Vol 7, 390.

[3] The Complete Sermons of Martin Luther, Vol 5, 14.

[4] Ibid.

[5] For more on Luther’s Hauspostille see Eugene Klug’s entire preface in The Complete Sermons of Martin Luther, Vol 5, 11f.