by Rev. Aaron Moldenhauer

König, Gustav Ferdinand Leopold. 1900. The life of Luther in forty-eight historical engravings. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 119

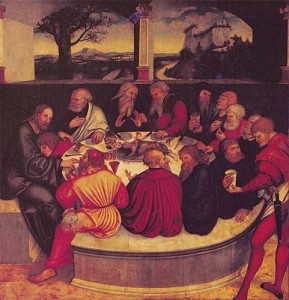

The presence of Christ’s body and blood in the sacrament of the altar was a matter of great debate in the early sixteenth century. Particularly in the 1520’s this question was fiercely debated among different Reformers.

Ulrich Zwingli, Johannes Oecolampadius, Andreas Karlstadt, and others offered arguments that Christ’s body and blood were not present in the sacrament of the altar. To cite just one example of their argumentation, they held that since Christ had ascended to the right hand of God, his body and blood were in heaven and could not be on earth. This was based on the premise that a human body could only be in one place at one time, and that a body could only be present in one sense, in such a way that the body occupies space and can be seen and felt.

Luther, writing against such theological claims, wrote several works on the sacrament of the altar in the 1520’s. Representative of these works is the 1527 book “That These Words of Christ, ‘This Is My Body,’ etc. Still Stand Firm against the Fanatics.” I survey a portion of that text here to give a sense of Luther’s thought on the presence of Christ in the sacrament.

All parties to the eucharistic debates of the 1520’s granted that God was present everywhere, and that Christ’s divine nature was present everywhere. Luther observes that God’s presence differs, however, in the person of Christ. God is present in his essence in all creatures. But in Christ God is present in such a way that one person is man and God. So we can say of any creature “God is in it,” but of Christ we can say “This is God himself.”[1]

Luther holds that the right hand of God is not a particular place where Christ is seated (as his opponents held), but God’s power. For this reason, as God is everywhere with his power, the right hand of God is also present everywhere. Luther grants to his opponents that Christ is at the right hand of God. But since the right hand of God is present everywhere, Luther takes this to mean that Christ is present everywhere. And, since Christ is God and man in one person, where Christ is there is also his body and blood. So, Luther holds, Christ’s body and blood are everywhere.[2]

Common experience, of course, suggests otherwise. Who has seen Christ’s body everywhere? More to the point, who sees it in the sacrament? Luther holds that Christ’s body is not present in a “crude visible manner, like bread in a basket or wine in a cup.” Nevertheless, Luther says, we believe that Christ’s body is present. This is possible because God has other modes of being present.[3] Luther argues from Christ’s post-resurrection ministry that his body was present in the same place as, say, the door of the locked room in which he appeared—it must have been present as Christ passed through that door. This presence is different than ordinary presence, in which Christ’s body would occupy space to the exclusion of other objects. From this Luther draws two conclusions: first that since this shows multiple bodies can be in the same place at the same time, it is also possible for a single body to be in multiple places at the same time. Second, Luther concludes that God and Christ are not far away but near. They do not need to move to be present with us, but they need only to reveal themselves.[4]

Common experience, of course, suggests otherwise. Who has seen Christ’s body everywhere? More to the point, who sees it in the sacrament? Luther holds that Christ’s body is not present in a “crude visible manner, like bread in a basket or wine in a cup.” Nevertheless, Luther says, we believe that Christ’s body is present. This is possible because God has other modes of being present.[3] Luther argues from Christ’s post-resurrection ministry that his body was present in the same place as, say, the door of the locked room in which he appeared—it must have been present as Christ passed through that door. This presence is different than ordinary presence, in which Christ’s body would occupy space to the exclusion of other objects. From this Luther draws two conclusions: first that since this shows multiple bodies can be in the same place at the same time, it is also possible for a single body to be in multiple places at the same time. Second, Luther concludes that God and Christ are not far away but near. They do not need to move to be present with us, but they need only to reveal themselves.[4]

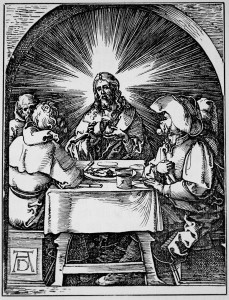

If so, Luther asks—if Christ’s body is present everywhere—then will I not eat and drink him in every tavern? Luther replies that even if Christ’s body is present everywhere, that does not mean that you immediately eat or drink or touch him. At this point Luther draws a distinction between God being present and God being present for you. Luther writes “[God] is there for you when he adds his Word and binds himself, saying, ‘Here you are to find me.’ Now when you have the Word, you can grasp and have him with certainty and say, ‘Here I have thee, according to thy Word.’”[5] In this way Luther moves beyond arguments about different modes of presence to ground the presence of Christ’s body and blood in the sacrament in the promise Christ makes in his word, namely, His word instituting the Sacrament. By his word Christ makes his body present for you in the sacrament.

The body that is present in the sacrament for you is there to nourish you spiritually. Luther takes it as a mark of divine grace that beyond being present with us everywhere, Christ offers us his body as nourishment. With this nourishment he gives us a pledge that his promise of eternal life for our bodies will come true, because our bodies partake here of an everlasting and living food.[6]

Luther’s writing confesses not only that Christ’s body and blood are present in the sacrament, but points also to the abiding blessings that Christ gives through that bodily presence. Christ’s body, present in the sacrament to eat, is a spiritual food that nourishes a person for eternal life. Lutherans agree on these fundamental and comforting points: Christ’s body and blood are present for you in the sacrament to give you forgiveness, life, and salvation.

The Rev. Aaron Moldenhauer is associate pastor of Zion Lutheran Church, Beecher, Ill.

[1] LW 37:63.

[2] LW 37:63-64.

[3] While Luther does not here articulate alternative modes, in other places he appeals to scholastic ideas about circumscriptive and definitive presence. Circumscriptive presence is being present in such as way as to occupy space, as a guard rail occupies space and prevents cars from occupying the same space. Definitive presence is being present in a defined place without occupying space, as a soul is present in a body or an angel is present in a particular place. Repletive presence is, for Luther, like definitive presence in that the body does not occupy space, but unlike it because there are no limits to the presence. A thing present in a repletive mode fills all things. See, for instance, LW 37:214-219.

[4] LW 37:64-66.

[5] LW 37:67-69.

[6] LW 37:71.